While on Prince Edward Island last week, I visited St. Dunstan’s Basilica (rebuilt 1916) in Charlottetown. On the front, it had the ancient symbols (drawn from the vision in Ezekiel 1) for the faces of the four evangelists carved in stone: Matthew = man, Luke = ox, Mark = lion, and John = eagle (the order from left to right on the building’s face).

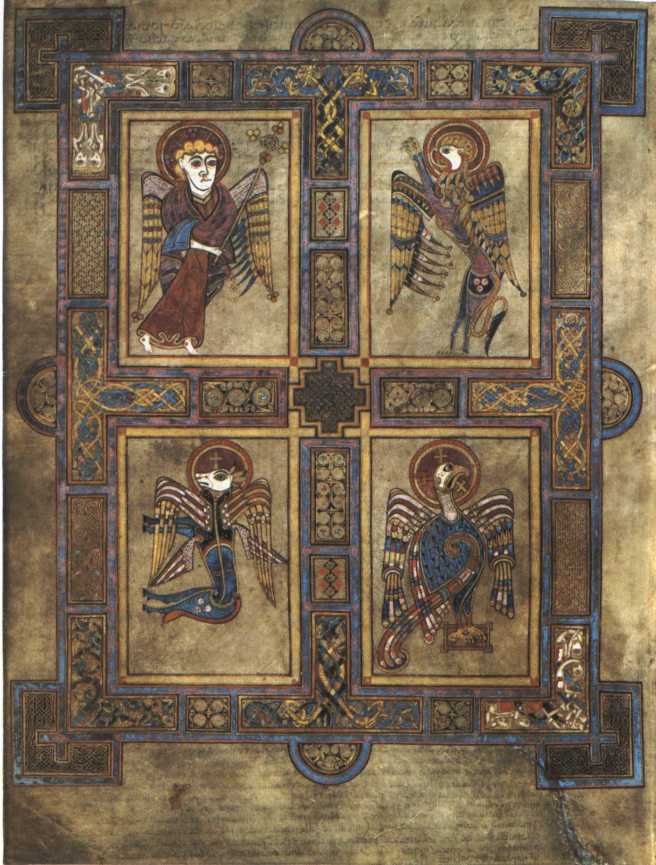

The order of the four evangelists here is unusual to my knowledge, but the symbolism for each evangelist is ancient. Here is the well-known page from the Book of Kells (fol. 27v; ca. 800): Matthew = man, Mark = lion, John = eagle, and Luke = calf (from top left clockwise).

This symbolism can be traced as far back as Jerome’s preface to his Matthew Commentary:

The book of Ezekiel also proves that these four Gospels had been predicted much earlier. Its first vision is described as follows: “And in the midst there was a likeness of four animals. Their countenances were the face of a man and the face of a lion and the face of a calf and the face of an eagle.” The first face of a man signifies Matthew, who began his narrative as though about a man: “The book of the generation of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham.” The second [face signifies] Mark in whom the voice of a lion roaring in the wilderness is heard: “A voice of one shouting in the desert: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.” The third [is the face] of the calf which prefigures that the evangelist Luke began with Zachariah the priest. The fourth [face signifies] John the evangelist who, having taken up eagle’s wings and hastening toward higher matters, discusses the Word of God (Thomas P. Scheck. Commentary on Matthew (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 117). Catholic University of America Press, 2008.).

But the symbolism in this period was far from fixed. Augustine had the following correspondences (Harmony of the Four Gospels 1.9): Matthew = lion, Luke = calf, Mark = man, and John = eagle.

The earliest Christian to draw the analogy between the Evangelists and the four living creatures in Ezekiel 1 was Irenaeus (Haer. 3.11.8; ca. 180), who had the following: John = lion, Luke = calf, Matthew = man, and Mark = eagle.

Why the symbolism? Jerome and others interpreted the faces of the four living creatures in Ezekiel 1 as a prophecy about these Four Gospels. Only these Four Gospels are compared to the four living creatures. There could and would only be these four despite the presence of other gospels in this period. By drawing the analogy to Ezekiel’s faces of the four living creatures, early Christians were claiming that only these four were authentic.

These arguments for these four gospels do not convince modern scholars, but all scholars are intrigued by them, for it is not altogether clear how Irenaeus appeals to the analogy. Is Irenaeus establishing a novel viewpoint by appealing to the analogy or is there precedent in the Christian tradition for only these four gospels that he defends by the use of the analogy? We can’t answer that question here, and much of it depends on how one reads the sources before Irenaeus.

When I was reading through the Old Greek (OG) text of the book of Job, the following verses (among many others, of course!) caught my attention:

When I was reading through the Old Greek (OG) text of the book of Job, the following verses (among many others, of course!) caught my attention:

Last week, I gave a presentation at

Last week, I gave a presentation at

We are in the third month since the release of The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis, and there are now two blog reviews and an amazing discount to report.

We are in the third month since the release of The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis, and there are now two blog reviews and an amazing discount to report. Yesterday, for any who missed it, over on the Oxford University Press Blog,

Yesterday, for any who missed it, over on the Oxford University Press Blog,  Although I haven’t blogged here in a while, I have been busy.

Although I haven’t blogged here in a while, I have been busy.